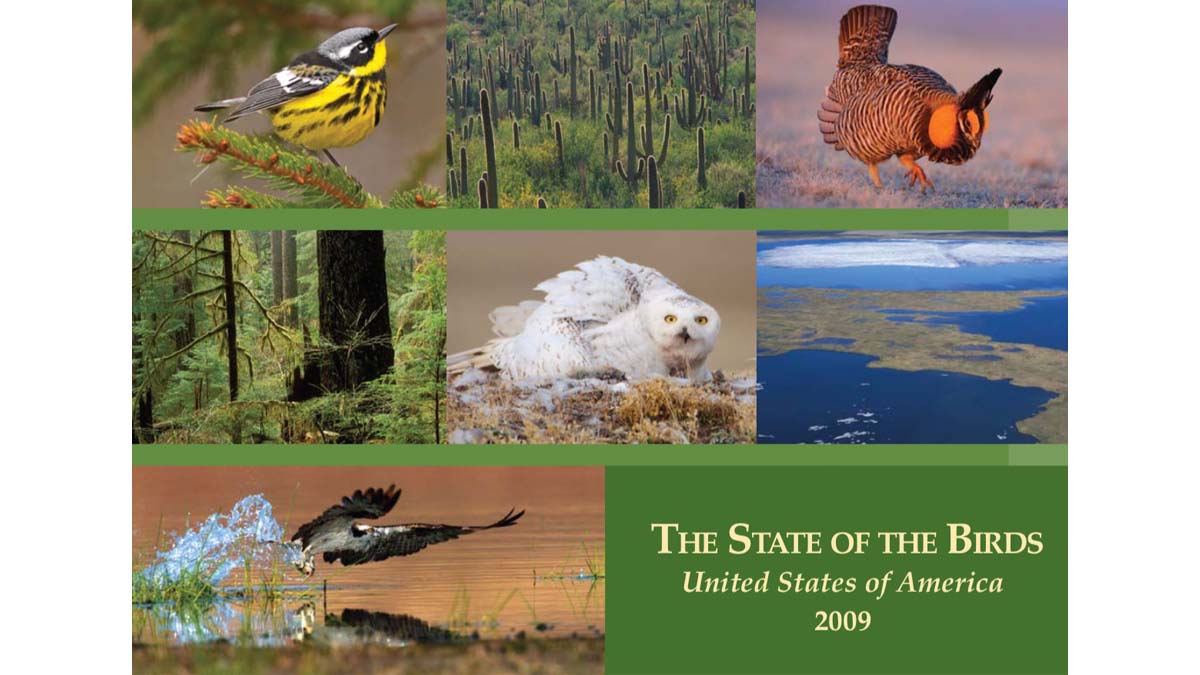

State of the Birds 2009 Report

Download the Report

Download a PDF of the print version of The State of the Birds 2009.

Some elements of the report were online-only and are not contained in the print version. You can still access PDF archives of the online version of the report, organized by report section: