Bird Habitat Can Put America on a Fast Track to Climate Resilience

In 2021, Audubon released a report that showed how bird habitat can also play a key role in sequestering carbon. According to the Audubon Natural Climate Solutions Report, the United States could realize nearly a quarter of its Paris Agreement commitment to reduce greenhouse gas emissions by protecting and managing priority bird habitats that will keep more than 100 billion tons of carbon out of the atmosphere.

Those priority bird habitats can also provide climate resilience in other ways—by mitigating against floods, purifying and storing drinking water supplies, and making our air cleaner. Birds bring money to the climate-resilience fight, too. Across America, there are numerous examples of how bird-conservation funding for restoring forests, grasslands, and wetlands can also strengthen our communities in the face of climate change.

Four joint ventures could offset emissions from every registered vehicle in NYC for more than two decades

Migratory Bird Joint Ventures are working across North America to implement national bird conservation plans at local scales, cultivating partnerships in the landscapes where they work to restore habitats for priority bird species. Joint Ventures can play a big role in the nation’s climate-resilience strategy, too.

Implementing just four JV habitat-conservation plans would yield the climate equivalent of removing the greenhouse gas emissions from more than 2 million vehicles per year over the next two decades—or every registered vehicle in New York City.

-

Appalachian forests by Via Tsuji/Flickr via Creative Commons. Restoring Forests in Appalachian Mountains

10 Million Metric Tons of Carbon

Implementing the Appalachian Mountains JV’s habitat-restoration objectives for Wood Thrush (a Tipping Point species) would restore forests across 150,000 acres of Appalachian woodlands from Georgia to New York. The restored forests will have high volumes of carbon sequestration and storage, as well as improved resiliency against disease and invasive pests. The AMJV’s plan will also add 4,000 Wood Thrush breeding territories to the region, while enhancing timber values on private lands and bolstering the Appalachians as one of America’s largest carbon sinks.

-

Bottomland forests by

U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service.Reforesting Bottomlands in Lower Mississippi Valley

59 Million Metric Tons of Carbon

The Mississippi Alluvial Valley has lost more than 80% of bottomland forests in an important region for migratory birds—wintering home for 40% of waterfowl in the Mississippi Flyway and breeding home for a third of the global population of Prothonotary Warbler. The Lower Mississippi Valley JV aims to restore 1.73 million acres of bottomland forests in Arkansas, Kentucky, Louisiana, Mississippi, Missouri, and Tennessee—enough habitat to support healthy populations of breeding forest landbirds and diverse waterfowl species while storing nearly 60 million metric tons of carbon.

-

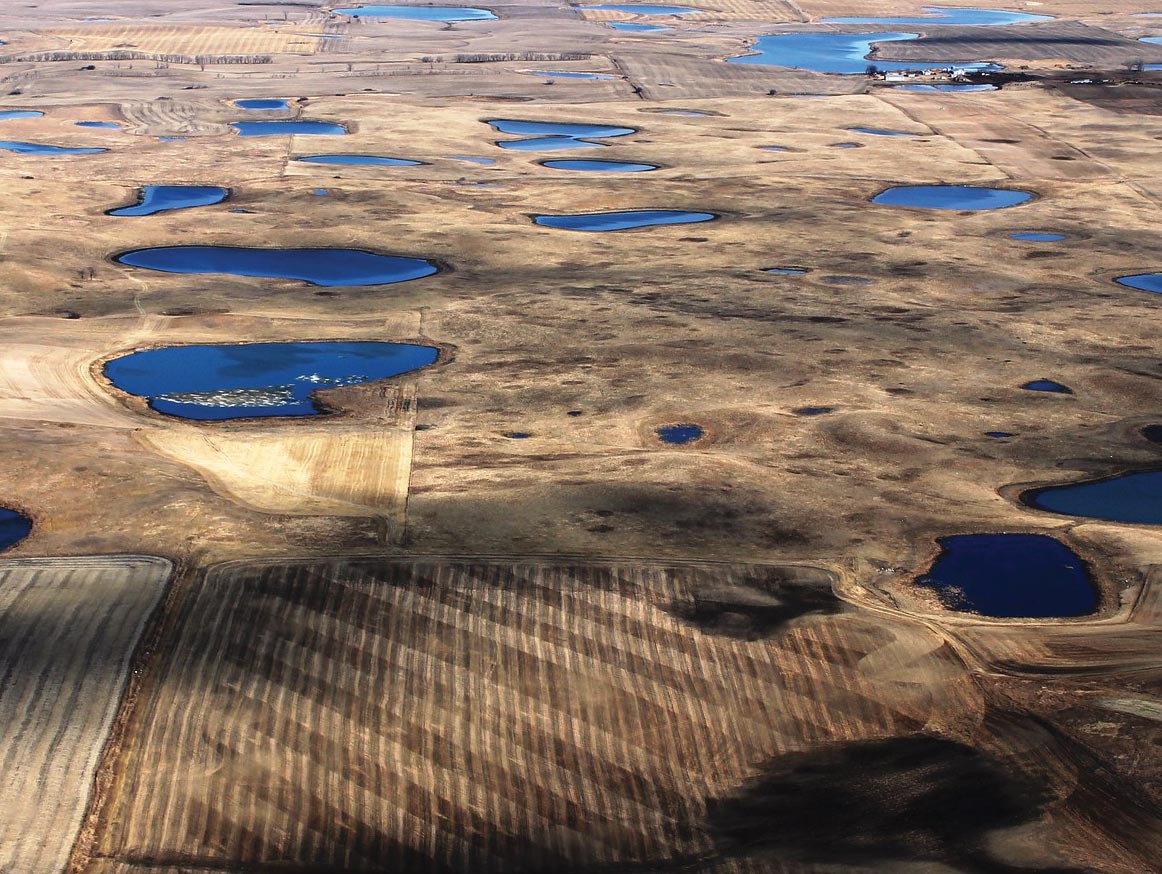

Prairie pothole region by U.S. Fish and WIldlife Service Mountain-Prairie. Protecting Duck Habitat in Prairie Potholes

7 Million Metric Tons of Carbon

The Prairie Pothole region is the most important breeding grounds for waterfowl in all of North America, supporting more than 50% of the continental duck population. The Prairie Pothole JV habitat plan is built around five primary duck species (Mallard, Blue-winged Teal, Gadwall, Northern Shoveler, and Northern Pintail) and calls for perpetual protection of 133,000 acres of prairie wetlands and 446,000 acres of native grasslands—adding to the vast carbon-capture complex in the prairie pothole landscape of Iowa, Minnesota, Montana, and the Dakotas.

-

San Joaquin River by U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service Pacific Southwest Region. Conserving Riparian Habitat in California’s Central Valley

7 Million Metric Tons of Carbon

Along the Sacramento and San Joaquin Rivers in California, birds such as the federally endangered Western Yellow-billed Cuckoo and Least Bell’s Vireo rely on riparian systems for breeding habitat. The Central Valley JV has produced a plan that calls for conserving more than 300,000 acres of riparian forests. Meeting the habitat goals for healthy populations of cuckoos, vireos, and many other bird species will also add to the buffers for local communities against river flooding and grow the Central Valley landscape’s capacity to capture and store carbon.

Vehicle emissions calculated using EPA Greenhouse Gas Equivalencies Calculator. Joint Venture carbon sequestration figures are calculated over 25 years, except for Prairie Pothole Joint Venture (20 years).

Accelerating a fire-safe future for Oregon’s forest communities

Throughout western forests, Collaborative Forest Landscape Restoration Programs (CFLRPs) have the potential to increase populations of at-risk birds, while decreasing severe wildfire risks for some of America’s most vulnerable wildland-urban interface communities. These fire-adapted forest landscapes historically burned regularly, but over the past 100 years such fires were suppressed and logging practices were largely unsustainable, causing fuel loads to build up. Now climate change is raising severe fire risks and threatening water security for communities such as Medford and Ashland in Oregon, which lie in one of the highest fire-risk landscapes in the Pacific Northwest.

These western forests also host a high diversity of at-risk bird species. The Partners in Flight (PIF) network developed a strategy to use forest management as a catalyst for bird conservation through forest restoration work that mimics the regular healthy wildfires of the past and mitigates severe fire risks in western forests. Working with the U.S. Forest Service and local communities through the Rogue Basin and Northern Blues CFLRPs, the Klamath Bird Observatory is leading the PIF effort to add bird-conservation science and funding into projects on national, ceded Tribal, state, and private forestlands. Projects involving forest thinning, strategic fuels reduction, and the reintroduction of wildfire through prescribed burning are designed to restore a mosaic of high-value forest conditions, while protecting old-growth forests and riparian areas.

By including PIF science in their planning, the CFLRPs have the potential to restore forests in a way that will reverse declines of Olive-sided Flycatcher and Rufous Hummingbird, as well as several other western forest birds in decline. By adding bird-conservation funding streams, the projects are designed to accelerate a safer future for communities who currently live at high risk for catastrophic wildfire, including the 100,000 people in Ashland and Medford.

Restoring playas for birds and water security in New Mexico

In 2018, the city of Clovis, New Mexico, estimated that if agricultural irrigation continued at the current rate, the underground drinking water supply would only meet community needs for about 11 to 25 more years. That year the city formed a partnership with Playa Lakes Joint Venture to include playa restoration in their plan to create a sustainable water future for people and birds.

Healthy playas—shallow, temporary wetlands found in the western Great Plains—are a primary source of groundwater recharge. Playas contribute up to 95% of the water flowing to the Ogallala Aquifer, which many rural communities depend on for their water supply, and they improve the quality of that water. However, many playas are no longer functional due to drainage and accumulated sediment.

Playas also provide important habitat for 185 species of birds, including Northern Pintail and Lesser Yellowlegs (a Tipping Point species). By working with state and local partners, Playa Lakes JV is blending bird habitat conservation and resilient communities funding to restore more than 4,100 acres of playas and surrounding grassland buffers in eastern New Mexico—enough playa wetlands to supply hundreds of millions of gallons of clean drinking water into the local aquifer for Clovis and other communities.

The PLJV model is so successful that it’s spreading, as communities from Kansas to Texas are now incorporating playa conservation into water security and sustainability planning.